As I sat in a theater filled with mostly middle aged festival goers, halfway through The Great Flood, I came to some conclusions:

As I sat in a theater filled with mostly middle aged festival goers, halfway through The Great Flood, I came to some conclusions:- Bill Morrison is THE filmmaker who could possibly settle the digital vs. film debate.

- People make their own stories, with or without a camera being present.

- Intent isn't always relevant.

All of the above.

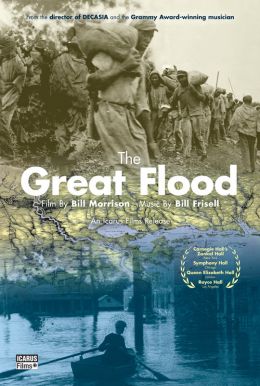

From the opening moments of The Film of Her, it's clear that Bill Morrison has a strong editorial eye for storytelling. His cinematic projects have all been "found footage", made up of lost, discarded and partially destroyed film. Morrison sees something special in these records of times gone by, and hopefully others do as well. His essays (or even abstract retellings like Spark of Being) come off as if we are entering the nether regions of someone's mind. Frayed and torn apart stock gives off a synapse vibe, popping and firing into other images. What sorcery of an autopsy is this?

Throughout The Great Flood, we get short breaks that inform us of the location/time of the following assembly of footage. The introduction is even sprawled over an old map, showcasing the Mississippi River region we are about to travel back to. These are the only moments of standard documentary form in the film, and while welcome, its almost unneeded. Almost.

Based on what I know, the footage in this movie was not chemically altered or damaged anymore than it had already been. The changes in texture and light, where images within the frame take on the illusion of moving to the forefront or background, were natural. Truly found. It's breathtaking how such sporadic effects - like when applied to people dancing or working - can be harnessed through cutting, trimming and syncing. This profundity can only occur withing the film format, and the conflicting contrast of textbook history with fading memories can only come from someone with that understanding. I'd rather hear from Morrison about the digital era of filmmaking than Tarantino.

Despite the horrific level of destruction documented in the movie, the people in these towns are shown smiling and making faces to the camera. At every turn, a young woman waves and a construction worker gives a grin. Of course, they must've been a bit (or a lot) miserable, but for the operating cameramen, people were either amused by the technology or knew that others would see this and chose to put on a face that the flooding couldn't take away. I doubt they had the foresight to imagine what their images would ultimately be used for, but in these moments, inner strength came out, and perhaps some relief was felt. Relief from a memory that could be passed on for some time. Even back then, people were forming history to tell a new story.

After my screening was over, I took to facebook to cement my earliest thoughts. I remembered how there was to be a Q&A with a historian, to discuss the real events. While it may have been illuminating, I don't believe that was the intent of the film, to be a supplement to a lecture. It wasn't so much a document of an event but a carefully constructed evocation of feeling. You understood what had happened and what was happening without the need for constant narration or any dialogue. This feeling opened levels of understanding with the people and places captured, more than any 3D projection or college grade lesson could ever try.

And please, do try.

5/5 *s

The Great Flood screened at the Louisiana International Film Festival this year.